Back to Guide to Collecting

Centering on Classic U.S. Stamps

Understanding why well-centered stamps from the classic era are so rare requires a look at the primitive technology used in early stamp production. Before the 20th century, postage stamps were printed and perforated using manually operated presses powered by water or steam engines, often in dimly lit buildings relying on oil or gas lamps. Given these limitations, it’s remarkable that any well-centered stamps from this era exist at all.

The Challenges of Perforation

The earliest U.S. stamps were issued imperforate, meaning they had to be cut apart with scissors. While experiments in stamp separation began as early as 1847, the first practical perforating machine was patented in 1853 by Irishman Henry Archer and adopted by the British Post Office. The United States followed suit in 1857, after a congressional mandate in 1855 made prepayment of postage compulsory, driving demand for more user-friendly stamps.

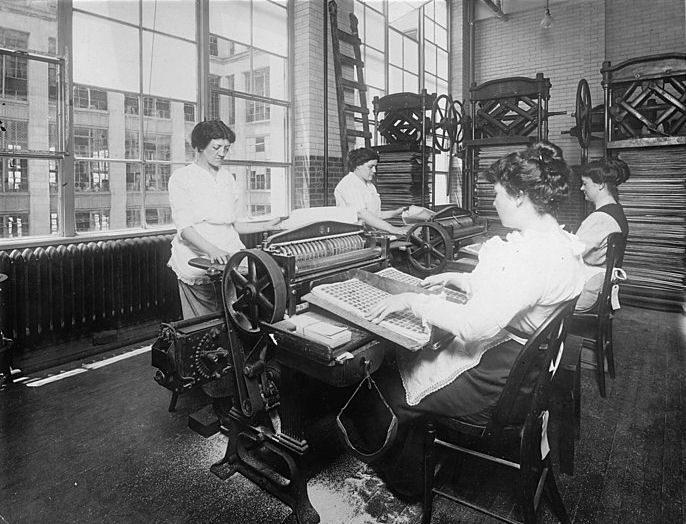

|

| Perforating stamps in 1861 |

The first U.S. perforating machine, based on British designs, worked by punching holes in one direction first, then rotating the sheet to complete the process. Since early U.S. stamps were rectangular, this meant perforation spacing had to be readjusted frequently or passed through a second perforator to ensure proper alignment. However, given the manual nature of the process and the inconsistencies in printing, perforations often encroached on the design, leading to the off-center stamps commonly seen today. Even within a single sheet, centering could vary significantly, especially if the sheet was slightly misaligned during perforation.

Manual Operation and Inconsistent Results

These early perforating machines required two operators: one to feed sheets into the machine and another to remove and inspect the perforated sheets. Powered either by steam engines or foot treadles, the machines operated under difficult 19th-century conditions, often with poor lighting. With no electric motors to ensure precision, spoilage rates were high—about 20% of a print run was typically discarded due to misaligned perforations. Even among stamps deemed fit for use, centering often fell short of modern standards. The primary concern of printers was functionality: stamps had to be easy to separate and suitable for mailing, rather than perfectly aligned for collectors.

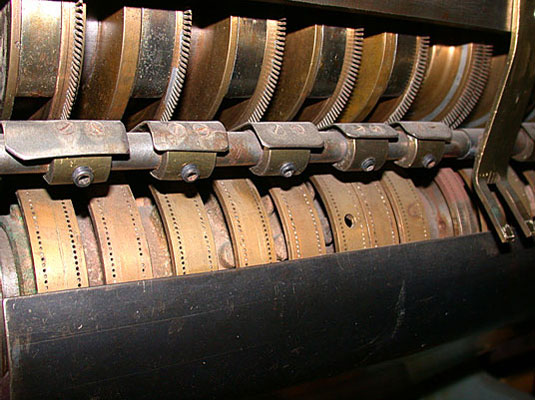

|

| Closeup of the adjustable cylinders in a rotary perforating machine |

Beyond perforation, the printing process itself contributed to centering inconsistencies. Engraved stamps required dampened paper to ensure even ink application, but once printed, the sheets had to be dried before gumming and perforating. Since paper expands when wet and contracts as it dries, shrinkage was not always uniform. Additional distortion occurred when gum was applied and dried, causing further curling and irregularities. So, a perforator calibrated for one sheet might be slightly off on the next, leading to subtle shifts in centering.

Improvements Over Time

For decades, perforation technology remained largely unchanged. It wasn’t until 1933 that significant improvements were introduced with the addition of electric eye markings—small guide marks that allowed perforating machines to automatically adjust for precise alignment. This innovation greatly improved centering and reduced spoilage, though even in modern times, misperforated or even imperforate stamps occasionally occur.

|

| Perforating stamps at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in 1914. Note the three "presses" along the back keeping finished sheets of stamps from curling. |

Given the technological constraints of the 19th and early 20th centuries, it’s no surprise that well-centered classic U.S. stamps are scarce. Most examples from this period exhibit what we now consider average to fine centering, with many showing perforations that intrude upon the design. While modern advancements have significantly improved consistency, early stamps serve as a testament to the ingenuity and craftsmanship of an era when every stamp was the result of a labor-intensive process.

Here are some blocks of classic U.S. stamps showing how centering varies among stamps in the same sheet: